Burns, Deep Partial-Thickness (Deep Second-Degree)

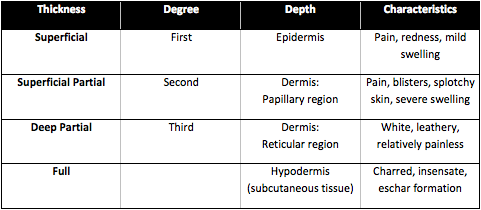

A burn is an injury to the tissue of the body, typically the skin. Burns can vary in severity from mild to life-threatening. Most burns only affect the uppermost layers of skin, but depending on the depth of the burn, underlying tissues can also be affected. Traditionally, burns are characterized by degree, with first being least severe and third being most. However, a more precise classification system referring to the thickness or depth of the wound is now more commonly used. For the sake of this article, burns will be described by thickness. For a comparison of the two classification systems, see the table below.

When burns extend through the epidermis and into the dermis, they are considered to be partial-thickness burns. The dermis itself is divided into two regions, the uppermost being the papillary region. This area is composed mostly of connective tissue and serves only to strengthen the connection between the epidermis and the dermis. Partial-thickness burns that only extend down to this layer of the skin are considered superficial.

The reticular region of the dermis contains not only connective tissue, but hair follicles, sebaceous and sweat glands, cutaneous sensory receptors, and blood vessels. Damage to this layer of the skin is classified as a deep partial-thickness burn, and can lead to significant scarring.

Another contributing factor to burn severity is how much of the body is affected. The "rule of nines" is a method of approximation used to determine what percentage of the body is burned. Partial- or full-thickness burns on more than 15% of the body require immediate professional medical attention. The following approximations can be used for adults:

- Head (front and back) ~ 9%

- Front of the torso ~ 18%

- Back of the torso ~ 18%

- Each leg (front and back) ~ 18%

- Each arm (front and back) ~ 9%

- Genitals/Perineum ~ 1%

Additionally, the palm (not including the fingers or wrist area) is approximately 1% of the total surface area of the body, and can be used to approximate noncontiguous burn areas.

Symptoms of Deep Partial-Thickness Burns

With deep partial-thickness burns (deep second-degree), the skin will typically be splotchy red or waxen and white, wet, and not form blisters. Blanching may occur, but color will return slowly or not at all. Depending on how much nerve damage has taken place, deep partial-thickness burns can be relatively painless.

Etiology

Deep partial-thickness burns can be caused by a large variety of external factors. The most common types of burns are:

- Thermal: Caused by fire, hot objects, steam or hot liquids (scalding).

- Electrical: Caused by contact with electrical sources or, in much more rare circumstances, by lightning strike.

- Radiation: Caused by prolonged exposure to sources of UV radiation such as sunlight (sunburn), tanning booths, or sunlamps or by X-rays, radiation therapy or radioactive fallout.

- Chemical: Caused by contact with highly acidic or basic substances.

- Friction: Caused by friction between the skin and hard surfaces, such as roads, carpets or floors.

- Respiratory: Damage to the airways caused by inhaling smoke, steam, extremely hot air, or toxic fumes.

Complications

- Infection: One of the main functions of the skin is to act as a barrier against outside infection. However, this physical barrier is broken with partial- or full-thickness burns wounds. With severe burns, hard, avascular eschar forms, providing an environment prone to microbial growth. In addition, eschar makes it more difficult for antibodies and antibiotics to reach the wound site.

- Circumferential burns: In cases where a full thickness burn affects the entire circumference of a digit, extremity, or even the torso, this is called a circumferential burn. These are particularly problematic because when relatively pliable skin is replaced by dry, tough eschar it can affect circulation to the distal area and result in compartment syndrome. To reduce the risk from the resulting edema, an escharotomy will be performed, making a surgical incision through the thick eschar down to the subcutaneous tissue.

- Hypovolemic and Hypothermic Shock: Other key functions of the skin are to regulate fluid loss due to evaporation and regulate body heat. When large areas of the skin are burned, the risk of hypovolemia (decreased blood volume) rises substantially and can send the patient into shock. Additionally, hypothermia is part of the "trauma triad of death" which, along with lactic acidosis and coagulopathy, significantly increases mortality rates in patients with severe trauma.

- Wound progression: Swelling and decreased blood flow to the affected tissue at burn sites can result in partial-thickness burns developing into full-thickness burns.

- Tetanus: Burn sites are specifically susceptible to tetanus. If the patient hasn't been immunized in the past 5 years, generally a booster shot is recommended.

Treatments & Interventions for Deep Partial-Thickness Burns

The three major goals for treating any burn are to prevent shock, relieve pain and discomfort, and reduce the risk of infection.

Small (less than 3 inches in diameter) partial-thickness burns:

If blisters are not broken, remove any jewelry or clothing from the area and run cool water over it for about 10 minutes. Take care to not open any blisters, as this will increase the risk of infection. If the blisters are broken, do not run cold water over the area and do not remove clothing that may be stuck to the burn surface. Doing so can increase the risk of shock.

Full-thickness burns or partial-thickness burns covering more than 15% of the body:

While waiting for medical professionals to arrive, start by ensuring the patient is no longer in contact with any burning or smoldering materials. Do not remove clothing that may be stuck to the burn surface, and cover the area with a sterile, non-adhesive bandage, a clean cloth, or a sheet (depending on what is available and how large the affected area is). Once again, be careful not to open any blisters. If the fingers or toes have been burned, use sterile, non-adhesive dressing to separate them. If possible, elevate the affected body part above the heart to reduce inflammation. If the patient is exhibiting signs of shock (clammy hands or feet, bluish skin tone, weak but fast pulse rate, rapid breathing, or low blood pressure) and hasn’t sustained a head, neck, back, or leg injury, start by laying them on their back. Elevate their feet about 12 inches to encourage blood flow back towards the vital organs and gently cover them with a coat or blanket to help stabilize their core temperature. Monitor the patient’s vital signs until medical help arrives.

The following precautions should be observed in dealing with any type of burn:

- Do not apply ice to the affected area. Doing so can cause further damage to the burn wound and increase the risk of hypothermia.

- Do not apply butter, ointment, petroleum jelly, oil, or grease on the burn. Not only do burn wounds need air to heal, but these also trap heat at the burn site and can further damage deeper tissues.

- Do not peel off dead skin, as this can result in further scarring and infection.

- Do not cough or breathe directly on the affected area.

References

Conrad M, Shiel WC, Wedro B. First Aid for Burns. MedicineNet.com. http://www.medicinenet.com/burns/article.htm#tocb. Accessed December 20, 2010.

Heller JL. Burns. MedlinePlus. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000030.htm. Updated January 13, 2010. Accessed December 20, 2010.

Mayo Clinic Staff. Burns: First Aid. Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/first-aid-burns/FA00022. Accessed December 20, 2010.

WebMD. Burns – Topic Overview. WebMD. http://firstaid.webmd.com/tc/burns-topic-overview. Accessed December 20, 2010.